-

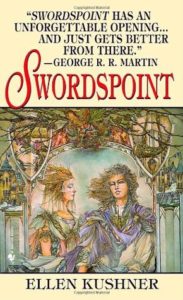

Review: Swordspoint by Ellen Kushner (1987)

“Above him, the stars shone frosty and remote in the clear sky. They wouldn’t dare to twinkle at him, not in the position he was in.”

– Swordspoint, Ellen Kushner

Rating: ★★★★★

Genre: Fantasy, romantic (but not a romance)

Categories: M/M, M/F, politics & intrigue, royalty and nobility, hidden identity, swords & swordplayContent Warnings (highlight to read): Frequent but not super graphic murder & violence. Recreational drug use. Discussions & ideation of suicide. Very morally ambiguous protagonists.

Description: A “classic melodrama of manners” where disputes are settled with sharp blades and sharper tongues. Swordspoint follows an interweaving set of characters and perspectives in a struggle for political power in the world of Riverside: Richard St Vier, an excellent swordsman but not much for conversation; Alec, his sharp-tongued lover with bad habits and worse ideas; Michael Godwin, a young lord who finds himself involved in games over his head; an elegantly powerful Duchess; and the rest of an engaging and largely morally ambiguous cast.

-

Review: The Merro Tree

5/5 stars. Buy at: Amazon

| Barnes & Noble | AbeBooks.com

(Note: This book is out of print but is available used at the above links)I first read The Merro Tree by Katie Waitman when I was fifteen or thereabouts, which I know for sure only because of the publication date (1997); I stumbled across it while it was still in bookstores, and I know I didn’t stumble on it late because after I read it, I checked bookstores for her name every time I went to one, which was at least twice a week, and this is how I came across her second book (The Divided, 1999). So I had to be 14 or 15.

I was in high school, and I had, at the time, a spare period right after lunch, which made it very easy to get a lot of reading done, and I assumed I had time to get through the rest of the book by then. I was almost right—I got through all but the last ten pages, when I had to go to my English class, which was taught by a diminutive, wonderfully kind but notoriously iron-willed woman named Ms. Saint-Pierre (everyone loved her, and yet, there were rumors—mostly spread by Ms. SP herself, I suspect—that the last student who talked too loudly while she was teaching class ended up dead in a stairwell).

At any rate, she usually started class off with warm-up/breathing exercises to get us in the creative spirit, so I tried to frantically read through the last ten pages hidden in my desk, because I literally couldn’t bring myself to put the book down. You need to understand that I wasn’t a standoffish student—I was eager to please, desperate to get high marks, and although I sometimes read in classes that I was very far ahead in, I only did it with a teacher’s permission.

Well, she noticed. “Put that away, Meredith,” she said, and, without meaning to, I blurted out:

“But I’m only three pages from the end!”

She stared at me for about ten seconds. I could see her feelings crossing her face: on the one hand, she’s teaching a class here, and needs the students to pay attention. On the other hand, the class she’s teaching is English: Creative Writing, and honestly, what is she even doing this for if not this?

“Well, hurry up and finish it then,” she told me, and went on with class.

This anecdote is partly because it’s one of my strongest memories of the first time I read this book, sure, but it’s mostly to illustrate how arresting it is. I had never done that before, and I never did it again, and when the words came out of my mouth I felt my heart just stop—but it was better that than not read it through to the end.

Anyway, the point is, I reread it over the last couple of days.

The Merro Tree is the story of Mikk of the planet Vyzania, a shy, self-hating, abused boy who becomes the galaxy’s greatest performance master (singer, actor, dancer, comic, instrumentalist—he can do it all) and, maybe more importantly, a self-confident man who can stand up for what he believes in. It’s a story about the nature of art and censorship and how the two intersect, and does so on a stage set out as a space opera. It stars almost entirely aliens (no human characters even appear until the halfway point of the story) and is nevertheless utterly relatable.

The basic premise is simple: Mikk is on trial for violating a galactic ban against performing a specific form of song-dance, and is trying to argue the ban as unjust. If he succeeds, it’s a victory for art as a whole; if he fails, the penalty is exile or death. This forms the frame narrative of the story, which weaves in and out with the life that has brought him to this point (a full 500 years time) and then, near the end—bursts free into an energetic present. The weaving of this narrative is, frankly, brilliant, because it manages to a) keep the frame consistent and chronological, b) keep the past consistent and chronological, and c) reveal things in each one that explains the meanings in the other in a fluid dance back and forth across that boundary.

It’s also a queer work in a time when there frankly wasn’t a lot of it. I didn’t find it because of that—although I did pick up a lot of queer books in my teens when I had first stumbled across some and was desperate for more, by virtue of finding a list someone kept on an old anime site and hunting all the works on it down—but I’d grabbed it off the shelf because it looked interesting. In typical style of the time, there was no mention of the queerness on the cover in any form (hence why I had to find a list for the others), so instead I got to stumble over it in a confused joy. The protagonist is pan or bisexual, in love with another male character (who is also a snake alien! Which, I mean, great, I am frankly here for this), and is nonmonogamous in a way that the book celebrates rather than going for either the ‘cheating’ or ‘scandalous’ route. Mikk’s love for Thissizz overflows constantly throughout the story, but Thissizz’s wives and Mikk’s other lovers are also celebrated as valuable, neither one threatening the other.

It’s not a perfect book—it’s a first book and it reads as such; the pov switches back and forth mid-section numerous times, and there are a number of tropes (the grotesquely fat villain, for one) and prose style traits that are pretty typical of 80s-90s sci-fi. The opening is also a little rough and hard to get into, because the switches between past and present need to be set up before they can start to inform anything. But none of this gets in the way of my need to give it five stars for what it does do, let alone what it did specifically for me. This book was a huge part of why I started writing.

It is, unfortunately, out of print, and I wish very much that someone would pick it up and republish it, because I very much want more people to read it and want the income to go to the author. I still check bookstores for her name every time I’m in them, just in case. And I hope you’ll seek it out anyway used.

It’s a book that deserves reading.

-

Review: A Tree of Bones

5/5 stars. Buy at: Amazon

| Barnes & Noble

A Tree of Bones by Gemma Files is the third book in the Hexslinger trilogy, with the first two being A Book of Tongues

(which I review here) and a A Rope of Thorns

(which I review here). I’m not trying to avoid spoilers for the first two books, only the third, so if you haven’t read the first two stop reading now.

So, to begin this review: aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaahhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh!!

Okay. Now that I’ve got that out, let’s do this properly.

After the horrifying outcome of A Rope of Thorns, the crew is left scattered across the land—and, in fact, across literal worlds. Chess Pargeter, last seen in hell, is trying to find his way back to his now Enemy-occupied living body, with only his abusive mother’s ghost as company. Ed Morrow is back working for Pinkerton, but a Pinkerton who has become a horrific soul-sucking artificial hex. Yancey is working with an unlikely group of hexes, struggling to use her skills to speak with the dead to be put to an unusual use. And, of course, Asher Rook continues to make only the most dubious of decisions while working for the wife-goddess who he has come to loathe.

If this wasn’t a perfect book—and I’m sure it has to have flaws, though I’m hard-pressed to find them immediately upon putting it down—it was close enough to it that I can’t even consider not giving it a 5/5 rating. The now-enormous cast all worked, everyone’s motivations driving their actions and knitting a good dozen B-plots together into the A-plot in a way that left me guessing right up to, and in some ways even through, the climax itself. The first book started with a small band of narrow-minded white men telling their own story while Othering everyone around them, and blossomed, over the next two books, into a bigger picture where a wide array of humanity were claiming their own stories and clashing together however needed to do so. I’ve been reading on my lunch breaks, but the story was too intense, and I actually neglected doing my own writing in favor of just finishing it off in one go tonight.

In almost every way—I’ll get back to that in a moment—this is the story I had hoped it would be from when the first bad decisions began. I’m not a fan of grimdark, I think I said in an earlier review, but this story struck me as something that wasn’t grimdark. It was grim, and it could occasionally be gritty, and by god, it was visceral, full of blood and guts and sex and pain. But all of that is fine, if the message of the story isn’t hopelessness. And it’s not. It’s a story about redemption, a story where bonds are important from start to finish. It’s a story where you know from the previous books that even death isn’t the end to a person’s story, nor what they’re capable of—and by God, if you had any doubt in that despite Chess’s first resurrection, Files makes sure to start you off on that foot with Chess’s trip through the underworld and the chance to see the continuing stories, good or ill, of the people he meets there. Because of that, the stakes are able to be high and include death of a variety of characters without the usual problem of killing characters off—which is that death, in most stories, is the end. It can be a powerful tool in an author’s arsenal, because a dead character causes the readers’ shock at that character’s potential cut short, but it also means broken storylines, never to see an end. Starting from a premise of underworld gods and souls that have their own business, just not with the living most of the time, means that the same thing can be used for the same impact in the story but without the same cost. It was still high stakes, and still worth mourning, but you-the-reader knows that some part of those characters may have some conclusion to their emotional story at some point, even if we don’t see their personal afterlife journey.

So ultimately it walks the edge of violence and pain and high stakes and loss without losing forgiveness and hope and redemption as possibilities for any of these characters.

I said above that there was one thing that wasn’t what I hoped it would be, and it’s involving a specific romantic subplot. I’m going to avoid details for spoilers’ sake, but the way it had concluded surprised me, given how it had been set up and was developing. I think it absolutely could have given me that payoff that I had personally hoped for, from what had come before. But—and here’s the big but—just because it could have, and just because it was how I would have preferred it to end, didn’t mean that the way it played out wasn’t equally possible, taking all the circumstances into account. I’m sure some part of my heart is going to hope that some time in the unknown offscreen future, when things have been dealt with and settled more, the possibility could be there again. Pity my shipper heart! But at the same time, what did happen was fine too, and worked with what the story gave us, and on top of that, it opened other doors too. I was content with it, even if it wasn’t the outcome I had personally hoped for. As Chess Pargeter would say, if things weren’t the same, they’d be different.

One of the themes of the story is that very thing—that there are multiple possible outcomes to situations, because people drive their own stories, and if things don’t happen one way, they’d have happened another. The way everyone’s stories come together and diverge, their lives playing out as their own motives push them forward, fit that perfectly; the author picked a hard, hard theme to embody through the story itself, but succeeded at it admirably.

I feel like I have so much more to say—goodness, but I want to write an essay about Asher Rook and how his choices spun out of his traumas and fears!—but a review isn’t the best place for that. So I think I’ll just leave it at this:

I’m glad I read this, and I highly recommend it.

-

Review: A Rope of Thorns

4.5/5 stars. Buy at: Amazon

| Barnes & Noble.

Please note that this book is the sequel to A Book of Tongues

, which I reviewed here. There will be spoilers for A Book of Tongues as a result.

In Gemma Files’ A Rope of Thorns, Chess Pargeter has a fresh new batch of problems in his life, as any new-minted demi-god is likely to have. As his old lover Reverend Asher Rook builds up “Hex City” as both a refuge for magicians (who are otherwise forced to feed on each other’s powers) and a place to sacrifice them to the newly-embodied goddess Ixchel to build her power, Chess goes on the run, Ed Morrow sticking to him fast and loyal. Soon joining them is a young spiritualist lady, Yancy Colder, whose temper and stubbornness is something even Chess can admire. But Chess himself, a hardened killer, is finding that even if his heart is gone, his heart might have survived more than he thought was possible.

First up, I want to say that this book definitely solved, for me, most of the concerns I had with the first one. It kept the strong writing and incredible characterization, but where there was a dearth of characters of color or female characters to narratively counter to the characters’ prejudices in book one, there are plenty more in this one (and only more upcoming, as I plunge headlong into book three even as I work on the review for book two). There are still characters’ casual slurs and assumptions in the narration, so fair warning to brace yourself for that if needed, but the narrative presentation of these characters supports them as individual characters with rich inner lives.

I don’t think it’s speaking lightly to say I loved this book. The narrative was clean and the story’s throughline was coherently built. The characters drove the plot, including those who weren’t point of view characters; every character had their own motivations for how they were acting, and this built the story, rather than outside events happening to shape it. This is by far my favorite thing to read, because everything fits together so perfectly.

And through this whole thing, bad and good decisions and damaged reactions and all, it’s an exciting Weird Wild West adventure with plenty of action, high stakes, revenge, bloodshed, sex, passion, and, yeah, the first strides toward redemption.

Normally I try to space my reviews for a series out, but this one came right after the first because I admit I literally just couldn’t stop reading. If that isn’t a rec, I don’t know what is.

-

Review: A Book of Tongues

4/5 Stars. Buy at: Amazon

| Barnes & Noble

A Book of Tongues by Gemma Files is the first book in her Hexslinger series. Let me borrow some of the back cover’s excellent summary:Two years after the Civil War, Pinkerton agent Ed Morrow has gone undercover with one of the weird West’s most dangerous outlaw gangs—the troop led by “Reverend” Asher Rook, ex-Confederate chaplain turned “hexslinger”, and his notorious lieutenant (and lover) Chess Pargeter. […] Rook, driven by desperation, has a plan to shatter the natural law that prevents hexes from cooperation, and change the face of the world—a plan sealed by an unholy marriage-oath with the goddess Ixchel, mother of all hanged men. […] Caught between a passel of dead gods and monsters, hexes galore, Rook’s witchery, and the ruthless calculations of his own masters, Morrow’s only real hope of survival lies with the man without whom Rook cannot succeed: Chess Pargeter himself. But Morrow and Chess will have to literally ride through hell before the truth of Chess’s fate comes clear…

This book is fantastic in so many ways. The writing is incredible—relentlessly sharp prose, deeply believable characters, and a fascinating magic system. It’s very dark and gritty, full of violence, death, and swearing, but it’s not what I’d call “grimdark”, not nasty for the sake of lifting up nastiness. All three of the main characters are absolutely understandable, even while I found myself begging them not to make the bad decisions they invariably end up making. Morrow is a genuinely good man with a strong sense of loyalty, lying to those around him for the sake of his job. Chess is hot-headed, amoral, violent, and loves to kill; he’s also hurt, in love, and afraid to make himself vulnerable even for a moment. And Rook is a once-good man who believes himself damned to hell, and makes choices, these days, out of his trauma and loss and self-hate more than he makes them out of goodness. Call them the good, the bad, and the ugly!

Plus, the book starts with a Wild West shootout over some men insulting Chess’s in-your-face homosexuality, and quickly proceeds to him making out with Rook over the bodies while Morrow stares in disbelief, which I’ve got to say is a real quick sell for me.

I’d have rated this a five out of five, except that it’s also an intensely uncomfortable read, and not just because of the very real hurt these characters visit on each other as they make bad choices. The characters are products of their time and place and are damned racist and sexist; the narrative follows the voice of whichever character is on screen, which is a very strong narrative choice when selling a mood or setting—but means we do see anti-Chinese racial slurs repeatedly in the narrative text itself, depending on which character is the POV character at the time. This might not be as uncomfortable if, for the duration of the first book, the story itself showed more to the POCs and the ladies of the text—but unfortunately, we don’t have any POC characters who are not in some way tropey to the setting (opium dealers or users, prostitutes, mystics, etc), and I don’t believe there’s a single female character in this book who isn’t evil, doesn’t get hit in the face, and/or isn’t killed. Nor are any of them important to the story bar the main villainess.

Now, some of it is called out narratively, via a character’s condemnation of white people and some other references to their biases that crop out throughout, but it was still a big lack in the book, and I wavered for a long time over whether I should rate this 3 or 3.5 instead of 4/5 rating. I actually read partway into the next book before writing this review to check it was a continuing problem or one the author recognized, since that might tell me if the “hints” I was picking up were there or if I was just reading into it because I wanted to believe in this—and, at least halfway through the sequel (which is as far as I have read at this point), it no longer seems to a problem to the same degree. The Chinese wizard we have met previously gets an actual name rather than just the one white people use for her and we see some of her thoughts and feelings in the prologue; the protagonists are also joined by a new female POV protagonist (of Jewish descent!). Since it seems to me like the author was setting up the characters’ close-mindedness through the narration in order to deliberately open this up throughout the series (and here’s hoping it stays that way!), I settled on a higher rating—but even so, we don’t get it in this book, and I still want to mention it since there are definitely people to whom this will be more of a personal sore point, and I wouldn’t want them stumbling into it unawares.

That said aside, coming back to the good: The narrative frequently jumps around in time in a way that I think some people could find off-putting, but it worked for me because it tells a nonlinear story by creating the emotional storyline separately from the narrative timeline, and choosing to follow that emotional storyline instead. I think that it wasn’t always successful with these choices due to small flaws (for example, if Chess says “Don’t leave me” at x later point in time, and y earlier point of time that we read afterwards references those words, the first conclusion is it’s chronological, not that he’s said it more than once, so that’s a place I got tripped up in understanding when sections were set). But it was successful more often than it wasn’t, and seeing a story prioritize building the emotional story over a chronological one was a fascinating narrative experiment.

I can’t stress enough how rich the text is, and how quickly I came to love these characters—massive warts and all. It was a fascinating, engaging read, and I’m very interested to keep reading; I’m completely caught up in the story and very, very excited to see how it resolves.